24 November 2025

Article

49m², year 9, summer 2025 | An afternoon in Zaartpark with Maud van den Beuken

AN AFTERNOON IN ZAARTPARK WITH MAUD VAN DEN BEUKEN

On a sunny late summer afternoon I get to the location of 49m² in Zaartpark. I see nothing: no installation, no intervention in the landscape, nothing that appears to be art. I only see an unassuming unmowed patch of land, between the tall grasses other plants have found their place under the sun. There is also a young willowtree, with a sign that once must have had information on it, but has since been erased by the weather and time. This seven by seven meter field was Moud van den Beuken’s workspace in the summer of 2025, but instead of getting to work with the space that she was given, she examined what was already at work in that space, before the human artist intervened.

49m² arose when artist Gerrit-Jan Smit signed a contract with the municipality of Breda in 2016. This contract stated that there would be a demarcated patch of land, of seven by seven meters, where for the duration of 20 years, there would be no maintenance. The end of Maud’s working period marks the 10th jubilee, and the halfway point of the agreement. For her this was the reason to observe what has grown here in this time: what does it do with the plant life if maintenance stops? What species find a new place? What species have to give way?

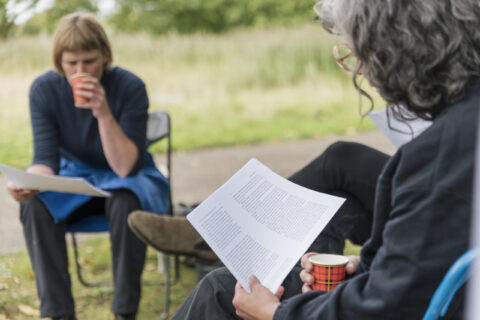

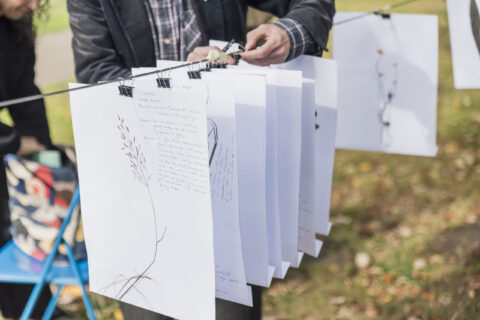

Back to my visit to Zaartpark: a little further on I run into Maud as she is hanging photo prints from a clothesline. Along the bank of the creek a few chairs are placed around a portable gas stove. I am invited to join a small group of interested people in exploring the 49m² area and this is our base. When all the preparations are completed, and the last participants have arrived, Maud asks us to join her in picking nettles. Back by the creek the gas stove turned on to make tea, and we can start the preparations for our expedition.

Looking

The act of observing plays a role in Maud’s work. Between 2015-2018 she made a series of cartographic photographs of the shy, with in the middle of every picture -invisibly small- the lens of the Landsat 8 NASA satellite telescope looking back at you. This satellite has been taking photos of the earth’s surface, for google maps amongst others. Between 2017-2020 she collaborated with a number of companies and experts to make scans of the Mississippi River, to visualise the invisible bottom and the transparent water through sculpture. She took these most recent sculptures on tour following the Maas, to observe in a series of public gatherings how a river is not only a physical, but also a social object through bringing together an involved interdisciplinary group: from climate investigators to harbour managers. In 2021 she built an observatory near Buitenplaats Brienenoord, where visitors can investigate the banks around the island in de New Meuse, Rotterdam. Every time Maug begins with looking, to go on to allow others to see what she has seen.

“Before I did anything, I wanted to see what was already there – what it is you are intervening with.” As a first step in her process, Maud invited Jaques Rovers from the Breda division of the Royal Dutch Natural History Society. With him she inventoried all the plant species in the little area. She collected all these species in an herbarium, images of which are hung behind us on the line. The multiplicity is flabbergasting. What at first seems to be a grassy field with a few nettles and one or two unfamiliar plants, turns out to contain about twentyone different species: “All of these plants tell us something about this place. For instance: the ground is quite wet, and definitely belongs to the river bed.” The little liver Aa of Weerijs is about 50 meters away, just out of sight. Maud grins: “After all these years I thought I would work away from the river for once, but it seems to be following me.” Through identifying and naming the different species, for instance using the internet, you can easily find information about a lot of plants, and the places they grow.

However, as Shakespere let Juliet question: What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by another other name would smell as sweet.” The rose in the forest doesn’t care what names we humans come up with to call it. You can learn the latin name for every species, but how much do you really learn from that about the plants in the field? The strange thing is, Maud observes, that when you have the scientific classification, you can learn and discover a lot, and you don’t even need the plants or the field anymore – you can stay behind your desk in your studio.

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger warns us about an overly techno-scientific approach to the world. Rather than being receptive to things as they appear to us, what he calls technology is a way of thinking that tries to grasp things by turning them into general concepts.Those who limit themselves to the technical perspective only see the recognizable and the predictable, and believe that this constitutes the truth. However, this requires ignoring the uniqueness of each place and each moment. It is preferable, according to Heidegger, to resign ourselves: we must let the world come to us and be receptive, instead of trying to control her. Although the technical approach is practical and useful, it estranges us from what is happening in front of us.

Brede Weegbree

Maud lets us read a passage from the book Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wal Kimmerer. Kimmerer is a native american botanist. As a university educated botanist she is familiar with the scientific names of all plants, but as a native she has also learnt a different way of connecting to nature. She writes: “I have noticed that as soon as some people know the scientific name of a being, they no longer investigate who it is.” Instead Kimmerer begins with giving names to the individual plants and trees around her: the spruce she encounters is no longer Pinea sitchensis, but strong arms covered in moss. And while the scientific name gives a definitive answer, she writes that the proper names she comes up with continually invite her to keep reconsidering: Are they appropriate? Are they still appropriate?

Just like Heidegger, Kimmerer is of the opinion that there is something alienating about the modern – western – way of thinking. Because of their conviction that they could control the land, the European colonist has never truly settled in the New World. She writes, it is as if the colonist has always kept one foot in the boat. When Maud questions how much you can know about a place through learning the names of the plants, I think she is referring to a similar kind of alienation: by holding on to Latin names, you are keeping one foot in the library. That is why her question during the working period became: how do you approach a relationship to a new place? A relationship that allows you to be present in a place and observe what you can see.

When the lecture is finished, Maud invites us on the expedition to that little field of seven by seven meters in Zaartpark. We each choose a plant and Maud asks us to not look up what they are called, but to observe and be inquisitive. What can we learn about a plant when we try to see the world through their perspective: how long have they been here? Are there many, or is it alone? What has their life been like – it is late September, most plants are already past the flowering stage, past the prime of their life. And what do they think of us? It is a way of thinking without pretending to what you are looking at. Instead of learning something new about this little field, a field I have notably visited before, I am learning mostly that I don’t know -and never have known- how much is happening here; and that I will never truly know. We can try to understand the world through giving everything a precise name, but that is likely to blind us. We would know exactly what can be seen, but we would lose who we have in front of us. The less we try to control, however, the more we can notice. Through taking us on this expedition, Maud invites us to pay attention to the many different creatures that have made these 49m² their home in the past 10 years: each with their own life and history, and all the relationships between them – and they didn’t need any municipal services or artists.

These days you hear a lot about invasive species, plants as well as animals. But there are a lot of species that are not native to The Netherlands, but were introduced by people like for instance the famously Dutch apple tree, brought over from Asia. What determines if a species is considered native or invasive, is if it was introduced before or after 1492 – before or after the colonization of America. Nevertheless there is another category next to native and invasive. Kimmerer speaks of a plant that carries the native name of White Men’s Footstep. This plant, in English known as the broadleaf plantain, hitched a ride in European bags of grain and bales of straw, and over the centuries has spread over the entire American continent. Instead of being invasive, the broadleaf plantain is modest and helpful: instead of being rampant it searches out nooks and crannies, and instead of disrupting the food chain it has medicinal properties. That is why the broadleaf plantain is not considered invasive, but naturalised. An invasive species tries to get a grip on the here and now by growing rampant and overruling, while being naturalised means that you perform humility out of respect for a deep history with an eye on the future.

When the lecture is finished, Maud invites us on the expedition to that little field of seven by seven meters in Zaartpark. We each choose a plant and Maud asks us to not look up what they are called, but to observe and be inquisitive. What can we learn about a plant when we try to see the world through their perspective: how long have they been here? Are there many, or is it alone? What has their life been like – it is late September, most plants are already past the flowering stage, past the prime of their life. And what do they think of us? It is a way of thinking without pretending to what you are looking at. Instead of learning something new about this little field, a field I have notably visited before, I am learning mostly that I don’t know -and never have known- how much is happening here; and that I will never truly know. We can try to understand the world through giving everything a precise name, but that is likely to blind us. We would know exactly what can be seen, but we would lose who we have in front of us. The less we try to control, however, the more we can notice. Through taking us on this expedition, Maud invites us to pay attention to the many different creatures that have made these 49m² their home in the past 10 years: each with their own life and history, and all the relationships between them – and they didn’t need any municipal services or artists.