12 July 2023

Article

49m2, year 7, spring 2023 | A Square Silence

A Square Silence

Britte Koolen is reading on a picnic blanket a few metres behind the 49m2 grassy area in Zaartpark, Breda. I walk up to her and greet her. Slightly confused, I look around: where is the artwork Britte created during her residency? I had expected to see one of her signature colourful geometric sculptures, but the grass appears empty. Britte notices my confusion and laughs. She invites me to walk a bit further into the park so we can talk calmly about her working period at Witte Rook. What follows is a conversation about her search for silence and the geometric nature of her art.

Reflecting on Silence

Once seated on the grass in Zaartpark, Britte explains that she decided not to place a work on the 49m2 plot. At the beginning of her residency, she thought, “there has to be a sculpture here, and it has to fit.” But over time, she realised that this mindset made her focus mainly on the deadline for completing the sculpture and the practical matters surrounding it. She began to question whether she would truly gain anything from the residency that way, and decided to take a different approach: she chose not to make a sculpture and instead immerse herself in the concept of silence.

Initially, Britte wanted to explore silence by striking up conversations with passers-by in the park: “I was really curious to hear how others perceive silence.” But that turned out to be more difficult than expected. Silence is a tricky subject, especially after the pandemic, when it gained an entirely new meaning. Her search for interaction with strangers gradually turned into a silent exercise for Britte herself – she focused on spending time in Zaartpark, reading there and seeking out silence on her own. Interaction with people would happen – or not. What she came to realise above all is that silence cannot be forced. She explains, “it doesn’t work to approach someone and then forcefully say, ‘Let’s talk about silence now.’” You can try to seek out silence, but it also simply has to be there. You can’t manufacture it.

Yet for Britte, silence is not merely the absence of sound. For her, it’s primarily a feeling of calm. “When I think of silence, I don’t even think of sounds. I think of a moment when everything is okay. When you, for example, don’t have any worries. Or that it’s okay to have worries. When there is balance.” Her need for silence and calm stems from the chaos that often takes hold of her mind. Britte shares that she’s experienced this since childhood: “Even when I was young, things could often feel very overwhelming, and I was always looking for something in the space where I could disappear. It could be a piece of chewing gum on the ground or a hole in the wall – something to focus on so I could momentarily escape the space.” That persistent sense of overwhelm is what now drives her fascination with silence. It’s a way of bringing order to chaos.

49 Times 1m2

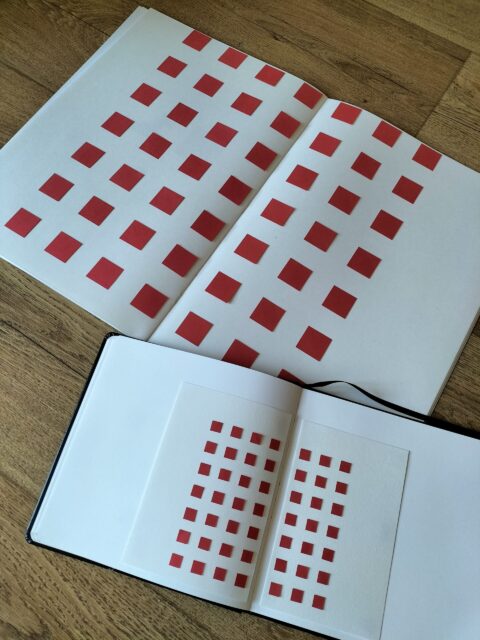

The visual language Britte uses to bring order to both her surroundings and her art is geometric by nature. She shows me the sketchbooks she worked in during her residency, revealing a universe of squares, circles, and lines. The 49m2 she was given immediately felt structured to her; she instinctively divided the surface into little blocks. 49m2 is 7 by 7, and even though the grassy field isn’t technically a square, Britte says she can’t see it any other way: “To me, it’s just 49 times 1m2.”

The order Britte creates in her work and sketchbooks is not necessarily aesthetic. What matters more is that the page feels ordered, regardless of any resulting geometric beauty. It must feel right to Britte, and beauty is secondary. She arranges her sketchbook pages the same way: abstracted and isolated shapes she finds in Zaartpark are drawn out of their environment, transformed as needed, and arranged on paper. While looking at her sketchbook, she explains that it’s also important to her that there is empty space on the page. Some people find emptiness unsettling; Britte finds it comforting. “I struggle to add things,” she says – every addition feels like an intrusion into the blankness of the page. And yet, it’s important to add something, because by placing geometric elements, Britte can give explicit shape to the surrounding emptiness. “If there’s nothing there, then it just remains nothing,” she notes. “You somehow have to make the emptiness your own” – and the same applies to silence, because “there can be no silence without noise.”

In her sculptures, Britte also seeks order and geometry – but, she emphasises, perfection is not the goal; it has to look and feel right. Her sculptures are never perfect geometric forms – her circles, for example, are never entirely round. That’s because Britte makes them by hand, a process that energises her and simultaneously serves as a moment of rest and focus. She thinks a lot while making, often discovering new shapes or negative spaces: “I use a lot of leftover materials, and that leads to new forms. If I make 49 circles, it’s not just about the circles, but also about the leftover wood. The arrangement of the circles creates space I hadn’t seen before. That experience disappears if you have the circles made by someone else.” The constant play between geometric element and negative space lies at the heart of Britte’s work.

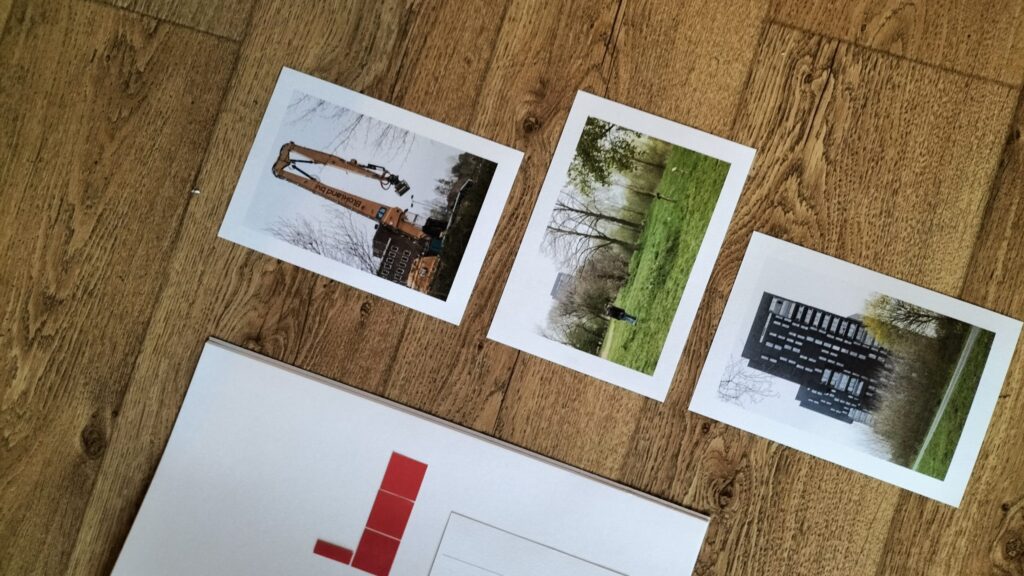

As Britte flips through her sketchbooks, it becomes clear that certain elements from Zaartpark recur: the block of flats at the park’s edge, the crane by the roadside, the bridge over the water, the 49-square-metre plot. Certain colours repeat too: red, lilac, yellow, and black-and-white. During art school, Britte often worked in black and white with a red detail, but nowadays red dominates. For Britte, red symbolises a point of calm within a space. That might seem contradictory – red is, after all, a bold and eye-catching colour – but for her, it’s the element she can lose herself in; a colour that still stands out in a chaotic environment, offering calm through its presence.

Not a Minimalist

At the end of the interview, there’s one more question I want to ask Britte: how do you relate to minimalism? One glance at her work makes the comparison hard to avoid. Her answer is firm: “I make minimalist art, but I’m not a minimalist.” Britte’s visual language indeed bears strong resemblance to the work of the minimalists, but the theoretical underpinning of her work does not. The principles minimalists use to create their work feel like restrictions to her – “a limitation I don’t want to impose on myself.”

Britte explains that her work is still very much developing. At art school, many tutors asked if she was sure about choosing this kind of visual language. They said, “This is very strictly minimalist work.” Now that she’s graduated and can dive deeper into her own practice, Britte sees that her work has softened over time. The cube used to be her anchor – the shape she returned to when she didn’t know what kind of work to make. Slowly but surely, she is now adding other shapes and colours to her palette: “I’ve been discovering more and more forms. The circle, for example, is now a beautiful, balanced form for me – it always continues and never stops. So perhaps my work has softened through the evolution of my visual language and the introduction of colour.”

Although Britte initially found it difficult to decide not to create a work for the 49m2 grass field in Zaartpark, she says she’s ultimately glad she made that choice. Her residency at Witte Rook gave her the opportunity to explore her own visual language and to research the concept of silence in peace. Her time at Witte Rook provided her with valuable insights into her artistic practice – and a wealth of inspiration for future work.

Charlotte Fijen, July 2023