26 June 2024

Interview

And then it turns out that something has changed, in conversation with Carien Vugts

The question of whether the myth of artistry has now been stripped of clichés and the unshakeable conviction of the sovereign creative urge, will not be answered in the conversation with artist Carien Vugts, sitting at the table of her temporary home and workplace in Zundert as Artist in Residence of the Van Gogh House. Although all the ingredients are present in the form of following in the footsteps of Vincent van Gogh as the personification of the mystery surrounding the visionary artist, Carien powerfully summarises the moment as a “Fuck You” attitude towards her own visual and artistic process.

I don’t hear that often. What led up to you feeling that way?

I applied for this residency a year and a half ago, when my work was undergoing a process of change. Until five or six years ago, my work was about nostalgia for physical places in my childhood home and my memories of them as a child. I created installations that told my story about this, and I integrated them into the space. I also used elements from my childhood home, materials such as wallpaper borders and baguette mouldings. And that was good; I did it with passion and expression, almost obsessively. I created those works based on my feelings; when I felt calm inside, I knew I had captured it well.

The process of change began in 2018 when I started practising Vipassana meditation. This form of meditation involves a “by-catch” that purifies traumas and conditioning that have built up throughout your life. While meditating, I encountered a childhood wound. It was a mild form of emotional neglect. It came about because I was very emotional as a child, and my mother didn’t know how to deal with that. As a child, I was completely unaware of this, and when I found out, I lost that feeling of homesickness that plays a role in my work.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

And what were the consequences of that?

Actually, something had already started to change in my work in 2019; the colours I used had become more muted, softer, you might say. In 2020, this process suddenly accelerated due to a three-week Vipassana retreat, which was followed five weeks later by the first lockdown. To tell the whole story, I was also involved in the Drawing Inventions Academy (DIA) at the time, where artists could immerse themselves in drawing. It was a crisis; I didn’t see anyone in person because my studio is in my home. Working in a studio is very similar to meditating; both require concentration and awareness, so what had been set in motion during the meditation retreat gained momentum. At the same time – several months had passed – I had committed myself to that master’s programme in drawing and had to produce a drawing no matter what, because that was what was expected of me. Instead of weaving with wallpaper and processing ceiling parts, which I normally chose as my material, I started drawing myself. And I began to combine the different drawings associatively, like a collage. I received good reactions at the presentation, so I continued with it and made a lot of drawings, which were very figurative. My work had always been figurative, but stylised and more based on contours and narrative. Now I am working with a lot of detail.

And looking back on that, what was the biggest change in your work?

Those three developments together – meditation, lockdown and drawing – triggered a kind of reset in my head, which in turn had an impact on the work I was doing in my studio. Looking back, I was drawing myself outwards through the influence of the meditation process and the letting go of traumas and conditioning. Half-hidden faces also appeared in the drawings. At one point, there was a drawing of a woman whose face was fully visible. It felt as if I had drawn my alter ego; someone who was free from those traumas and conditioning and was claiming her place. It was all very confusing for me, but I continued to draw and the associative process did not stop. They became figurative stories with incredibly more colour and detail.

And now you’re here as Artist in Residence in Zundert, where the narrative revolves around Vincent van Gogh, but with a “Fuck You” attitude. How did that come about?

I continued to draw through all the ups and downs, so it became lighter, then darker again, or even malicious in tone. All I could do was go with the flow, with all those emotions, but I no longer had a story. Not like I had before about the nostalgia for the locations from my childhood. That feeling had been purified by the meditation process. I now have a process – of meditation – that also guides me visually. I usually have confidence in that, but the outside world wants a story. While the story is not always there, sometimes there is only the process that dictates what I have to do. Even though I don’t always know if it fits into art, it still has to be made, and that is my “Fuck You”.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

What was your initial plan that you wanted to explore during this residency?

My plan here was to explore the change in myself – and within myself – in relation to Vincent’s fluid touch. How he managed to capture the changeable fascinated me, and I realised that he worked so quickly and under psychological pressure and restlessness. And now I’m sitting here, which I couldn’t have known when I applied, while I’ve – hopefully – already gone through the most intense part of my process of fears and anger. From this, I concluded that I could no longer find Vincent in my process. So what am I going to make? Instead of fear and anger, I am now equanimous. But then there is the fear that the source will dry up: “What if the meditation process is ‘complete’ and there is nothing left to be said?” What do you make as an artist then?

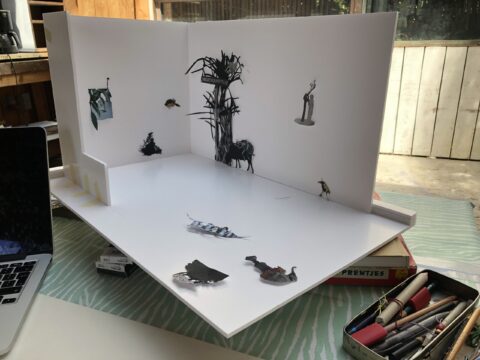

I had to get rid of that fear, so I started to explore the surroundings. I went cycling, walking and familiarised myself with all kinds of things in the area, and then it turned out that I could do it. During a previous residency, I worked in the studio from the first day to the last. What I didn’t do then, but do now, is allow myself the freedom to search here for something that makes me sufficiently an artist. And then it turns out that something has changed: first I created work from within myself, and now I bring it in from outside. And yet it produces an exciting image.

And what attracted you, or struck you, in the surroundings? What inspired you?

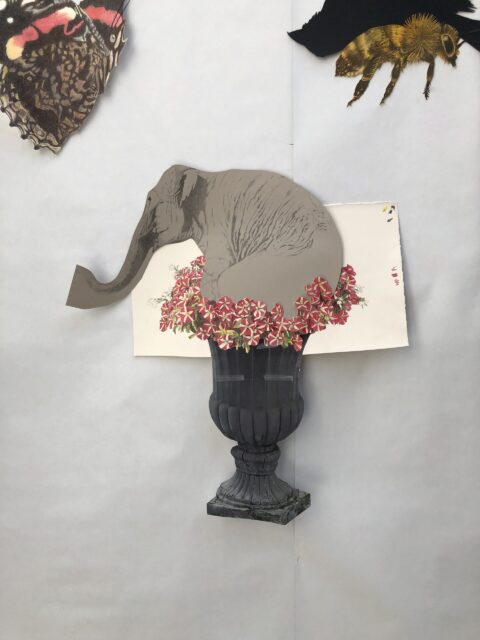

Various things: trees, animals, raked gardens with pots of petunias. Of course, I didn’t find that elephant in the work with the flowers in the surroundings. It arose from a kind of jubilant mood because I now have the freedom to create this, but is it art? It’s the first time I’ve asked myself that question about my own work. I also wonder if it’s a good piece of work, and even now, what art should be. But it just happened. How do I explain that? Maybe you should think of looking at holiday photos at home and wondering why you actually took that photo. It’s more about capturing your inner mood at that moment.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

And what else did you see?

What I also found here was purgatory. While cycling, I came across a street called Vagevuurstraat (Purgatory Street). How remarkable! Contrary to what most people think, purgatory is not the place where the choice between heaven and hell is made, but rather the place where your sins are washed away. Purgatory can therefore be seen as a metaphor for my meditation process, in which equanimity and “ultimate freedom” are the ultimate goals.

At the same time, you also drew a statue of Christ and a church. Does that have anything to do with religion?

No, not necessarily. The Sacred Heart statue stands outside the church in Achtmaal. This statue has a stump because part of its right arm has broken off. In the cemetery next to the sexton’s house here, there is an old weeping tree. Vincent’s father planted it when his eldest son – also named Vincent – died at the age of one. This tree also has a kind of stump because it is a grafted tree. I have connected these two stumps. It is more of a connection through sadness.

I chained the church because I also wanted to include architecture. I can see this church from the window of my studio, but I replaced the church spire with an elephant on a ball. That’s something we think of when we think of elephants, such a big, clumsy grey creature balancing on a ball. But that’s impossible, and that’s why you can’t find it anywhere. I searched everywhere on the internet. Well, with one leg on the ball. Still, the idea comes from somewhere. That’s why it’s a recalcitrant work for me, but I don’t think anyone else sees it that way.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

What will you take away from this work period?

I am pleased that I can work without being obsessive. I have taken trips myself. That gives me more space and confidence in the artistic process. That it will continue and that I should create what I see fit. I decide what will be created, although I am touched when people have opinions about it. And also that I can be inspired by my surroundings and that the source can lie outside myself. This is the very first time I have experienced this and am certain of it. Before, I thought: “I am a finished artist”. Whereas being here has given me so much, by being open, being in a different place and being able to relax. This gives me a lot of confidence for the future.