Although Jarik Jongman “is not particularly interested in Vincent van Gogh’s life”, his fascination with his death is all the greater. The last weeks that the illustrious painter spent in France coincide – coincidence or not – with the period that Jarik is staying in Zundert as Artist in Residence. Now, some 134 years later, Jarik had conceived the plan to devote himself to artistic research in Vincent’s birthplace into how Vincent’s own life ended dramatically after painting his last work: the tree roots. This provided fertile ground for new ideas, and it was not so much death as resurrection that became a theme.

How come your initial plan to explore Vincent’s death in greater depth changed so much?

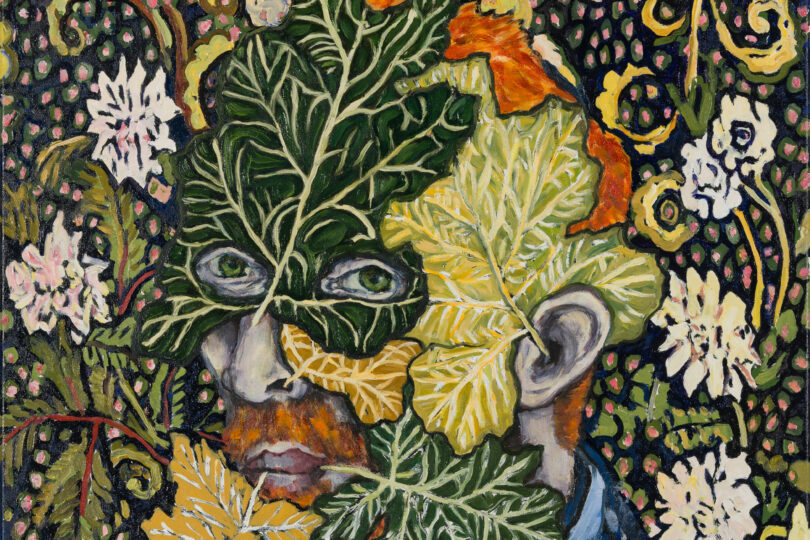

I wanted to do something with Vincent’s last words: “la tristesse durera toujours”. Vincent shot himself in the fields of Auvers-sur-Oise, but he did not die immediately and returned to the village to die. However, I had written my proposal more than a year ago. In the meantime, I did some research and came up with another idea. His last painting, which he made there shortly before his death, is of tree roots. When I looked closely at the print of that painting, I saw his face in those roots. With a little imagination, you can see his eye, nose and ears. His portrait is thus part of the painting, which I find beautiful. It is as if he has made his own death part of his work and that nature and life itself come together through him.

And that’s how I came across the story of the Green Man. A phenomenon that originated from a pagan symbol, which can also be found in the Christian church. It is very old; the oldest image they have found dates from 200 years A.D. It is an ancient god of vegetation, of nature, a myth in which the hope that spring will come again plays a role. The green man is often hidden in churches, in the decorations and ornaments of the building or in the wood carvings. In Breda, there is also one in one of the choir stalls in the Grote Kerk. It is a symbol of resurrection, but also of death. That was entirely appropriate for this painting and for Vincent; not only because he had a strong connection with nature, but also because death was part of his being.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

And how did you connect this mythical figure to Vincent? Even though Vincent van Gogh has also become a mythical figure, it’s not really comparable.

The term Green Man became popular in England in the 1930s; they really made it their own. There are numerous places and pubs called Green Man. As a symbol, the Green Man is very beautiful and is in line with the Egyptian god Osiris and the biblical Lazarus; it is about resurrection and the cycle of life. Vincent also painted Lazarus based on an etching by Rembrandt, or rather himself as Lazarus. He was, of course, also religious and even wanted to become a minister. I found it funny that, in addition to his love of nature, he also had a thing for resurrection. I combined those two things. First, I painted Vincent as a green man, based on existing portraits of him with acanthus leaves on his face. These leaves are often used in classical Greek and Roman columns and in classical architecture. They are prickly, thorny leaves, associated with the difficulties and trials of life. At funerals, they were used to honour the deceased who had gloriously overcome these difficulties.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

And how is that reflected in the works you have created here?

I had already done some preliminary work at home. I wanted to get a lot done and not leave everything to this month; what if I got stuck… The portraits I made of Vincent are based on his own works and then as Green Man, but they also have backgrounds that come from Vincent’s paintings. That’s from his French period, with patterns like in La Berceuse and The Postman. I adapted them a bit. Normally I do that first with Photoshop, but now I do it while painting.

And you’ve also created a very large work. Was it created here?

The Vincent in the large painting is a Pictor Mundis, like Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundis. My initial plan for this painting was to continue with Vincent’s coffin, but when Ron and Eva* told me that this is the year of the sunflower, I changed my plan. So no coffin among the sunflowers, but Vincent as a green man among the flowers. In his hands you can see a painter’s knife and a palette, so you can recognise him as the painter, but otherwise he is covered with ivy growing out of his mouth and ears. And that has to do with the image you see here in the studio. It’s actually a mannequin. I’m a painter, not a sculptor, but in order to create a sculpture, I coated the mannequin with flammable sealant and then worked on it with a blowtorch before coating it with ash. The idea is, or was, to grow sunflowers in it and then let them die; dead sunflowers are really dramatic. The volunteers planted sunflowers for me, really big ones, but I hadn’t taken into account that they don’t bloom until September, so that’s not going to work now. Hence the ivy, which are cuttings brought back from France from the grave of Vincent and Theo, his brother. I will place this sculpture in the Van Gogh gallery after the work period, lying down, with the ivy growing out of it. I will have to buy some more because there is not enough. And the ivy will have to be guided upwards. Because the Van Gogh House will be staging an exhibition about Vincent’s sunflowers in September, I will show this sculpture again, but then according to plan with the sunflowers that are now growing. I have also bought 100 kilos of sunflower seeds, which I will scatter on the floor of the gallery. I have no idea how that will work, whether it will be too much or too little, or whether people will slip on it. They are black, though, so that fits the image.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Apart from experimenting with physical images, did you also try out new methods as a painter?

I usually work with Photoshop to create a digital sketch that I use for painting, but the nice thing about a residency is that I can now experiment with that too. For example, I have made a number of digital compositions, using photographs, which are now at Hema to be printed. I will paint on those. They are compositions similar to those now hanging next to the large painting. Preliminary studies for this work. The prints also include images I used from Julian Schnabel’s film about Vincent van Gogh. In this version, he did not commit suicide, but was shot by two boys. In this narrative, the famous line spoken by Vincent, “no one is to blame but himself”, refers to this act. But however interesting that theory may be, I am mainly interested in the scene with the coffin, of which I have made screenshots. It is a composition of the coffin with Vincent surrounded by his paintings, on which I still want to paint ivy. Maybe it will work, maybe it won’t, but that’s the experiment.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

And after a month of Vincent 24 hours a day, time for something else?

I am far from finished with Vincent and the sunflowers. But now it’s time to go outside and explore the neighbourhood and take photographs with the aim of creating an artist’s publication. That’s not for now, I’ll continue with that later. I’m also fascinated by X-ray photography. How they use it to find different images hidden in a painting, which is also what Vincent did. How the frame of the canvas also becomes part of the image. I have worked with this concept using mono prints and oil paint. First, I make the background black and then paint on the material on which his works are printed with white paint and print it with a roller or by walking over it. This creates such ghostly images. I’m not sure what to make of the discovery of earlier works through X-ray photography. There must be a reason why he painted something over; do we really need to know everything? Although that might be strange to say in a residency that is about Vincent van Gogh and focuses on research. What would Vincent think if he knew that the whole world was reading his letters and diaries?

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Is what you have created here in line with your previous work?

These portraits featuring Vincent and the acanthus leaves as the Green Man do not fit in with this. I copied his work for that, and even though it becomes your own interpretation, when you repeat his brushstrokes, you are copying him. That is why I am glad that the leaves are covering it, breaking with that. The fact that I now do nature-related things is more or less coincidental. Previously, I made works based on war and history, although, as now, they were also about the environment. Still, I have also done things with plants that take over things, so it’s nice that that theme is coming back. But in terms of style, I am now a bit more expressionistic, perhaps because of Vincent. Like him, I also use more contours in these works. I think I make very different work, yet I hear that people recognise my style. I get bored with things quite quickly and then I try new things. Lately, I’ve been combining figurative with abstract. Completely abstract doesn’t suit me, it’s not my thing, although that may still come.

Finally, have you changed your mind about Vincent?

I started thinking about him! And how he became the prototype of a romantic artist because we made him that way.

Photo by Jonathan de Waart

*Ron Dirven is director and Eva Geene is curator of the Van Gogh House and the Van Gogh Artist in Residence.

Esther van Rosmalen, July 2024