12 June 2025

Article

In Proximity Of – On Schimmenspel, a video installation by Iratxe Jaio and Klaas van Gorkum

The significance of an institution can be measured by the size of its archive,

a truth that certainly applies to the copyist program of the Prado Museum in Madrid. Ana Maria Martín Bravo wheels a cart into the climate-controlled documentation room, adjacent to the museum library. The cart holds five large registration books and a white cushion. A few months earlier, Iratxe Jaio had visited this very archive as part of the research residency she undertook with her partner, Klaas van Gorkum, at the invitation of Witte Rook.

Witte Rook is a platform for research, experiment, and reflection in the visual arts, based in Breda. In the autumn of 2023, they asked Jaio and Van Gorkum for a contemporary perspective, as artists, on the shared Spanish and Dutch history. Renowned for their long-term, research-based projects at the intersection of anthropology, sociology, archaeology and visual art, the duo chose to focus on The Surrender of Breda by Diego Velázquez, and in particular, the many copies of this painting located in various semi-public locations in Breda.

Submitted by participants of the exhibition Marrying for Las Lanzas: Married couples Lucia and Chris Strous; Harrie Pulles and Ria Embregts

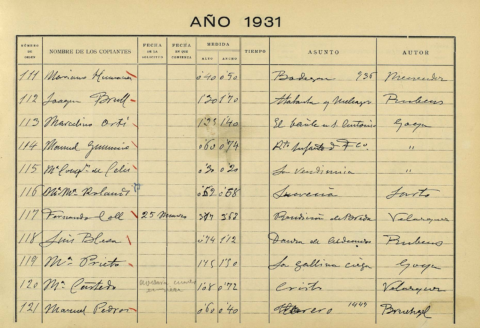

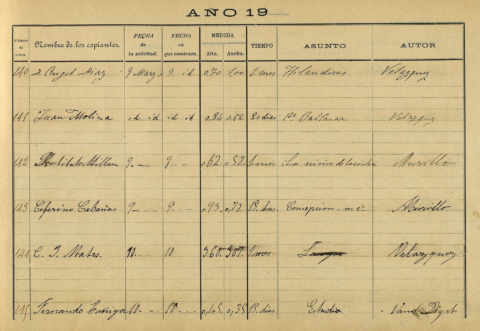

Ana Maria places the cushion on the immaculate table, presses a hollow into its surface with her hand, and opens one of the books within it. I look down at the yellowed pages: rows of artists’ names, titles of paintings, and the dimensions of the canvases they carried. Several months earlier, Iratxe had combed through these books to track down the signatures of the copyists responsible for replicas now spread throughout Breda and Helmond: in the Castle of Breda, the Castle of Helmond, Stedelijk Museum Breda, and the City Hall.

The artists approached the replicas they found at these locations less as artworks and more as artefacts – real fakes, in their words – objects that not only frame social interactions but also subtly structure them. At each site, they filmed how people moved, waited, posed, or otherwise performed in the presence of the paintings.

The resulting footage formed the basis of Schimmenspel, a three-channel video installation. The ongoing soundtrack suggests continuity between locations, causing the distinction between the different spaces to dissolve. Instead, what emerges is a strange, hybrid space where real and unreal, ignoring and posing, theatricality and documentary intertwine – with the painting serving as a motif that interconnects all scenes.

The choice to focus on The Surrender of Breda is anything but arbitrary. The painting depicts Justinus of Nassau handing over the keys to the city to Ambrogio Spinola, marking the end of the Siege of Breda. Yet the handover takes place on a hill that does not exist in Breda. Velázquez never visited the city. He based his composition on a play by Calderón de la Barca. The Surrender is therefore not an accurate rendering of a historical event, but a representation of a representation.

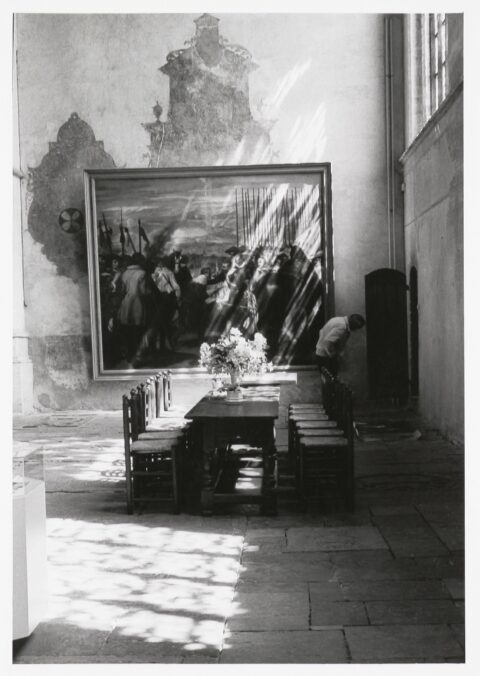

Photo from the City Archives: a copy of the painting Las Lanzas in the Grote Kerk, 1990, painted by Kees Maks

This layering of representation,

where each new stratum moves further away from the original event and in doing so raises fundamental questions about how meaning is constructed, is central to the work of Jaio and Van Gorkum. Meaning rarely declares itself. Rather, it accumulates like sediment that builds up layer by layer to form the basis for different kinds of interaction. In Schimmenspel, the distinction between original and copy therefore matters less than what these works bring about: how they derive value from the social and spatial contexts in which they operate, and the forms of engagement they make possible.

One such form of engagement is physical proximity to the subject. “It’s a way of connecting with these people,” Iratxe told me during one of our phone calls, “and of giving the research a bodily dimension. We found a great deal of information online, but the experience of seeing those books – especially the signatures of the copyists – is something entirely different. It becomes a kind of contact object: something tangible that, through the archive, links you to other artists who’ve also worked with this painting.”

One everyday yet telling scene in Schimmenspel makes this idea of the painting as a tactile contact object concrete: museum technicians remove the canvas from the wall. One of them steadies it with her hand at its centre. Once it is laid on the floor, the stretcher bars, staples, and mounting plate that keep the canvas taut are revealed. Later, they rehang it for an exhibition on the House of Nassau at the Stedelijk Museum Breda. For a brief moment, the painting ceases to be a depiction of a military surrender and becomes, instead, an unwieldy object transferred from one symbolic space to another.

Photo by Iratxe Jaio & Klaas van Gorkum at the Stedelijk Museum Breda

Every attempt at exact reproduction is bound to fail,

or so the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges suggests in Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, a key reference point for Jaio and Van Gorkum. Borges wrote this short story in 1939, well before the structuralists began to challenge authorship and notions of authenticity. It tells of a 20th-century author who rewrites Don Quixote word for word, only to realise that, in a new historical and cultural context, his replica has become something entirely different.

And therein lies a certain power. Since 2001, Jaio and Van Gorkum have situated their practice within the understanding that replication inevitably involves transformation. They focus on monuments, handcrafted objects, bureaucratic templates, archival materials, and frameworks that shape public life. They question what happens when such bearers of meaning shift function or outlast the intentions that once defined them.

The museum copy is precisely such a form that has fallen out of step with its time and shifted in significance. Once a coveted status symbol, it now serves as a curious reminder of an era when art education revolved around mimesis: the belief that a painter’s skill was cultivated through faithful imitation of the Old Masters.

Ana María points out several names in the register: Manet, Courbet, Picasso – who, at the time, still signed as Pablo Ruiz. My eyes land on entry number 117: Fernando Coll, the same name Iratxe had come across here before. In 1931, Coll registered to copy The Surrender of Breda on a 317 by 367 cm canvas, commissioned for the service anniversary of Breda’s Mayor Van Sonsbeeck.

Signature of Fernando Coll in the Libro de copistas of the Prado Museum in 1931

“In the end, it’s not really about the painting itself,”

Iratxe said. “For the video installation, the meaning of the painting is both relevant and irrelevant. We treat it more as a MacGuffin – an excuse to document a variety of social situations.”

Even if the canvas is not truly the subject of Schimmenspel, it still functions as a connective element between different groups of people. The camera records how they relate to it: wedding couples posing with their families, just as hundreds have done before them, seemingly unaware of being filmed. Other groups, by contrast, are sharply aware of the camera. The group of students, for instance, look directly and suspiciously into the lens. One holds a megaphone – a nod to the squatter protests that took place in the 1970s, before this very painting. And then there are the three young military cadets posing before the canvas in formal readiness, doing their best not to smile. Later, they help take the painting down from the wall.

“We’re always aware that filming instantly creates a power dynamic between those behind and in front of the camera,” Klaas explained. “These videos examine that dynamic. They expose our own awareness of the filmed situation and reveal the layers that inevitably come into play when filming.”

One scene shows just how complex that dynamic can be: three women and a man stand with their backs to the camera, facing the painting. Then they turn and look directly into the lens. The woman in pink – whom I later learn is the Deputy Ambassador of the Netherlands to Spain – does so with effortless ease. She’s one of the few who seems completely at home in front of the camera, as if she’s long since mastered her place in the public eye.

Signature of Kees Maks in the Libro de copistas of the Prado Museum in 1906

Back in the documentation room at the Prado,

Ana María gently closes the register book and places the cushion back on the cart. As we walk together through the library to the foyer, she tells me that the archive relies on interested individuals to keep its knowledge alive.

“Saluda a Iratxe y Klaas de mi parte,” she says as we part ways at the exit.

“Claro,” I reply, shaking her hand before stepping out into the heat.

Beneath the shadows of plane trees lining the Paseo del Prado, it suddenly occurs to me that I never actually looked at the original Velázquez painting. For a moment, I consider turning back, but in the end I keep walking. Perhaps the fact that I never saw the original says enough. After all, Schimmenspel reveals how images shape us, even when we forget to look.

Madrid, June 6, 2025

The styling of the section titles is inspired by The Liverwort Who Wanted to Take Root (Chenta Tsai), The Long Form (Kate Briggs), and Blood and Soap (Isabel Marcos).