30 June 2022

Interview

Light, colour and movement by Studio KASBOEK

Long, long ago, when there was still a department store called V&D, three artists bought their ideal sketchbook there, which was actually a cash book. In the boxes where income and expenditure were usually recorded, they created fantastic new worlds that travelled back and forth between the different places of residence of Debbie van Berkel, Cathalijne and Jojanneke Postma, until they were allowed to leave the paper as an art project. Even though the cash book disappeared from the shop shelves, they remained faithful to the name by calling themselves Studio KASBOEK, and even had new copies made. Nevertheless, their beloved cash book was unintentionally forgotten when digital means tempted them to record their concepts in other ways, until Corona changed the world.

The Kasboek

Until 2008, Debbie, Cathalijne and Jojanneke each studied at a different art academy in the cities of Breda, Antwerp and The Hague. After that, the obvious question arose: what next? How does the art world work? How do you get into a gallery? How is your work seen? Is there really such a thing as a black hole? To take stock, they started using a cash book to make notes, send them to each other and set aside one day a week to exchange ideas that led to projects and exhibitions.

‘[Jojanneke] During the pandemic, we resumed our method of sketching in our cash book. Together, we are looking for constant development by sharing and complementing each other. [Debbie] Sometimes I see something that the others don’t see, and vice versa, of course. [Jojanneke] When you all look at the sky, you see the same thing, but then again, you don’t. You can never be sure that we all see the same thing. Biologically, that’s not even possible; every eye is different. [Cathalijne] At the same time, it’s mathematics; our brains are constantly organising, including our memories, and we can attach numbers to that. [Jojanneke] The digital revolution has shaped the way we see things, and we use that very consciously in our work. We don’t choose a specific medium or discipline, but colour, light and movement. We can use that to change perception – how you look at things. By working intensively with each other and growing in that process, we can also switch easily between different subjects. [Cathalijne] Collaboration gives you more confidence, and you need that confidence for large projects. It’s never the same, yet it’s always a continuation of what came before. [Debbie] It’s fun to discover something new every time. [Jojanneke] And that may seem simple, but it’s never that simple.’

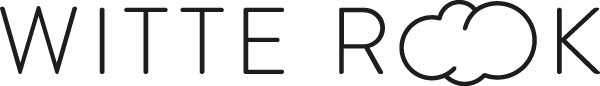

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Precious Stones

The reason for coming to Zundert as Artist in Residence is the cash book from Arles. Whether the discovery of 65 drawings by Vincent in the old inventory of Café de la Gare is fake or real is of no importance to them. What matters is the history of these evocative books in which the absoluteness of numbers is exchanged for the indefinable nature of the imagination.

‘[Cathalijne] We see Vincent as a fourth member of our collective. The idea was to use eye-tracking technology to see if we could read Vincent’s emotions in his portraits. It was fun, but it didn’t really yield anything, so we moved on to his letters. Vincent also achieved success through hard work, and that was something we could work with. [Jojanneke] And we linked that to our own motivation: here, you have the time to get started on that. [Cathalijne] It’s a journey of discovery; you go on a trip and meet people who want all kinds of things from Vincent. [Debbie] You meet the whole world that comes here. [Cathalijne] Vincent wrote about the starry sky that stars are like diamonds, but much brighter. In translations, these “star diamonds” are also called precious stones. That is why we have continued here with the R.E.T.I.N.A. project. These are RGB screen prints with special pigments that appear white, but actually contain many colours. We are collaborating with science because diamonds have the highest possible refractive index, but ours is slightly higher. The entire spectrum is contained within it. [Jojanneke] The way our eyes work can be compared to digital processes, and mixing the digital and physical worlds creates other parallels. [Debbie] The digitally malleable world of retina.’

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Artificial Intelligence

Perhaps by chance, perhaps not, they chose three of Vincent’s masterpieces with the intention of using these paintings to align his way of working with their own. Vincent’s descriptions of the works, or the passages in which he expresses his wonder, are a form of memories that can be relived for them.

‘[Jojanneke] With Artificial Intelligence, we want to involve Vincent in our work in the here and now. [Debbie] With AI, you can combine all kinds of things, such as sketches, drawings and descriptions, and you can even generate new memories. What emerges as an image is a kind of painted digital photography. [Jojanneke] That also fits in with the changes in the brain and how we translate that back. [Cathalijne] The programme can process text and images and is set up to get the best out of them. [Jojanneke] The interesting thing is the combination of text, sketches and images. [Cathalijne] Images are created because you start to recognise the way of thinking. These are all snapshots. The most important thing is that the programme works hard and comes as close as possible to its task. We also deliberately chose this period because of the weather; June and July were the most productive months for Vincent. In this way, we use AI to create new paintings in which Vincent’s signature style is recognisable, but with mathematics and science, because it has to be related to us.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Cyanotype

To complete the circle, the digital images are also given a physical version. Using cyanotype, a photographic process that produces a cyan-blue print, the new interpretations of Vincent’s works reappear as reinterpretations. In addition to their desire to work with this light-sensitive material, they also feel it is important that both possibilities are represented.

[Cathalijne] But we also created an NFT, together with others who are familiar with the technology. I now also know quite a bit about AI and the way of thinking and sharing. [Jojanneke] The accessibility of knowledge and software is something that is currently being discussed, because how can you share something like that openly in the world? But it is important, think of the climate crisis and war situations. In any case, cooperation is necessary, and because art and science complement each other well, we are working together with Delft University of Technology. Where science stops, art can continue. [Cathalijne] It’s about chance, and how you experience it. [Jojanneke] Olafur Olafsson inspires us to seek overlap and understanding of and for others. [Cathalijne] The interesting thing about an NFT is that there are as many possibilities as there are opinions about what you are actually buying if it is not tangible, but technology is already everywhere and it is just there. As an artist, you have to take that into account. And now there are finally platforms for artists who work digitally to sell their work, although of course there is a lot of rubbish among it. [Jojanneke] The beauty of an NFT is that there is a fair distribution of resources because you also get a percentage when it is resold. The computer gives the impression that everything and everyone is equal, but people are not that transparent. [Cathalijne] The month here in Zundert was a marathon. We are still so much in the development phase that even one more day would be nice. The intensity of the coronavirus period makes it even more special to have a focus on our own development at this moment and in this place. It won’t stop either; there will definitely be a sequel to continue with the colours we learned about through Vincent.

Esther van Rosmalen, 30 June 2022.

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen