1 December 2022

Interview

The living organism of the Zundert soil, Loran van de Wier

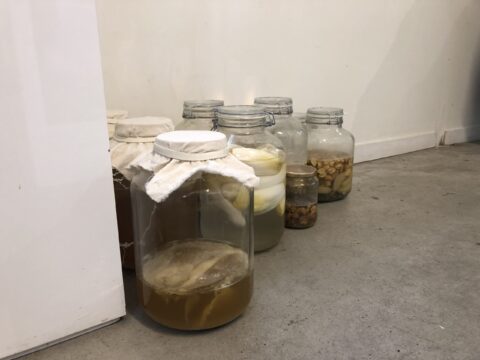

Traditionally, the month of December at AiR Van Gogh is reserved for alumni of the St. Joost art academy. This time, the winner of this residency is artist Loran van de Wier, who has made not only the studio but also the kitchen of the guest house his workplace. Many jars of preserved food occupy the windowsill, table and floor. He is not a prepper or an activist world improver, but sincerely believes in the small steps he can take as an artist and as a human being by consciously dealing with one of the essentials in life: our daily food.

Step 1: Visit the farmer

Potatoes, chicory, cabbage, carrots, mushrooms, tea, pak choi, rutabaga and cauliflower are neatly arranged in rows, ready for consumption in transparent preserving jars or pots with gold-coloured screw caps. And even though winter isn’t really the most logical time of year, everything really does come from the land, provided it’s from Zundert.

“If you do it right, you can grow vegetables from the land all year round. These are the harder varieties such as pak choi, rutabaga, or kale. I think it’s important that what I use is also from here, which in turn tells a lot about the environment. For example, I was able to get fresh lettuce from the vegetable gardeners, while I met someone at the hobby farmers who grows green vegetables together with people who are distanced from the labour market. It’s intensive and hard work, but also beneficial for people with addictions, for example. The stories behind the food here are fascinating.

There is also agriculture that is quite industrial and not really accessible. I suddenly find myself there for a few heads of chicory. Not every grower is passionate about their product; sometimes it’s about other things, such as production processes and business operations. This has to do with an unfortunate combination of trust and distance. Think of the supermarkets: these big players determine the market, and as a result, food producers lose touch with the people who consume their products. The “organic” label is another example. Organic doesn’t have to be more expensive, but our system isn’t suitable for small farmers. Supermarkets don’t want that kind of vegetable. No label means no control. The difficulty isn’t in growing the produce, but in being locked into the market. There is a need for labels because people no longer see the nuances.”

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Step 2: Processing and fermentation

Loran can put together a complete menu without a refrigerator. Through fermentation, or the controlled spoilage of fruit or vegetables, he can preserve them for a long time and even create new flavours. He ferments both wet and dry ingredients in jars. In the latter case, he only adds salt to the vegetables before sealing them so that the vegetables release their moisture. While a layer of perishable white mould appears to form in the other jars, this is not a problem; it is simply the result of fermentation by lactic acid bacteria, which eat the sugars and leave behind a sour taste.

“Actually, you can’t go too far wrong with vegetables. I open them regularly to release the pressure and taste them, but the fermentation process continues and I don’t stop it. Rice and grain are difficult processes that can make you ill. Animals also require many more steps, which are too complex and less interesting.

What is the difference between animals and plants? We take an animal into our home, give it a name and think we can control it. What is the difference between chicory and me? I talk and think, which chicory clearly does not do, but it also has the will to live. My work explores the question of why such a distance has developed between humans and plants. Putting it in a pot makes it look like human or animal remains preserved in formaldehyde. It is almost repulsive, as it resembles body parts. But it is a plant. That is the mirror I want to hold up.

The bottom line is that we need to change the way we interact with our environment. It is primitive to think that there is not enough food; on the contrary, there is a ridiculous amount of food if we live according to the seasons. Summer is the season of abundance, intense, fruity and floral. In winter, there are hardy and strong varieties. For example, a white cabbage will remain intact for two months if you throw it away, but that knowledge has completely disappeared.”

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Step 3: Eating together

The studio is the starting point for the dinners that Loran has organised around his residency, with the gallery, the kitchen and even outside at the cemetery being the locations to which he takes his guests, including previous artists in residence, on an exploratory journey to discover a new variety of food. Everything that this earth has to offer is present, although unfortunately the invited farmers and growers did not come.

“Still, I want to get them involved in the future. I notice that a group of people who don’t know each other beforehand still come into contact with each other. Although I do wonder what it actually is – the dinner – a ritual or a performance? I don’t know. It is enjoyable, even though I sometimes serve them difficult flavours. The order is therefore very important; for example, chicory and mushrooms are the most fermented, so you eat them in the middle of the meal.

Of course, we also talk about big things. If I have to choose between the Anthropocene and the Symbiocene, I hope for the latter. We’ve come this far, so we can still work it out together. Texts and sources that I use play a role in the conversation, such as those by Richard Sennet. His perspective is very fundamental: what is ritual and what is tradition? Consumption, being together, preparation? But I want to keep it small because the big picture is interesting and at the same time it isn’t. For me, activism is political, and I don’t need to promote that in my work. Raising awareness of what food does, what taste is, getting people to think and act differently, that’s what matters to me. The power to act lies in the 30 people who ate together last month.”

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Photo by Esther van Rosmalen

Step 4: Make it communicable

Each dinner is captured at the end with a photograph. The moment when the reason for the gathering – the food – is inside the people and the experience is reflected. What is different this time is that the film camera is now also part of the dinner and is passed around to the participants. Some of them zoom in on the food, others make their own choices about what to capture, all in one take.

“The presentation is a reflection on the work process and shows what is interesting to show. I don’t know if all the stories are that important to tell. I’m not there in the gallery either, so the recording can take over. Now I’m editing it, not too much, just removing the superfluous stuff. The film is not the end goal either; seeing a fragment is enough because it’s really not the intention that you watch for eight hours.

What I do may seem fairly obvious; it’s nothing new in the kitchen, nor in art. It can sometimes feel difficult to move between these two worlds, which is different from someone who creates art with a capital A. The contrast between chef training and art school is huge, from working with your hands to thinking. Yet the process of cooking is no different; the way of working is stable and I can vary it. For example, I am considering collaborating with a filmmaker to bring film and food together as a vehicle for the story, but that is for the future.

I am spending the last week painting to translate my experiences of the past month. Painting is something that works well under time pressure and has become a big part of representing my process. As with cooking, I know what goes together without having to think about it. For me, the working period consisted of reading, driving around for vegetables and cooking in the kitchen. Kitchen or studio, for me, these are not separate entities, and that’s how it went: everything intertwined, which was fascinating. Just like working with Vincent’s native soil, his colours, his vegetables.”

Esther van Rosmalen, December 2022