On a rainy afternoon, I started my journey with a walk along an alley of old willows. I passed a few busy streets, buzzing with cars and then eventually, I arrived at the entrance of the StadsGalerij in Breda. I got warmly greeted by artist Daniel Ventura and crossed the threshold of the building. I always believe that entering an artist’s work space is such a unique experience. It opens my mind to new possibilities of interpretation. It also teaches me as the spectator about the mind of the creator and how they think or who they are as a person. A work space is an intimate look into an artist’s heart. It becomes an even more intriguing phenomenon, when an artist joins a residency program and transforms given space into their asylum but only for a certain amount of time. That is exactly what happened in the case of the Mexican artist Daniel Ventura.

P: What was your motivation to come all the way from Mexico City to Breda? Was there any specific reason?

D: ‘Nothing really specific. I tried to do my research to find the next location that would be important for my professional career. I used to just search online for residencies. To me, it’s a way of continuing my contemplations about the meaning of being ‘in motion’ and in time. I was interested in residencies because it is an opportunity of being in a new place just for a certain amount of time. I came across the ‘Open Call’ at Witte Rook, around 3 years ago. I decided to participate, because as a rule, I try to find these opportunities that as a requirement have work with the environment, the city and the landscape. Since those are the main themes in my work, I decided to take part in it. To be honest, I didn’t know anything about Breda when I was applying, but once I got accepted to join the residency, I started doing more research. That is also how I got the idea to start working with bricks.’

P: Before we move on, there is a reference to a ‘Horizons project’. Could you tell a little more about it and explain the main concept of the project?

D: ‘I think it’s coming from a book that I read a few years ago. The book is called ‘The Man and the Earth: The nature of geographical reality’ by Eric Dardel (L’Homme et la Terre: Nature de la Réalité Géographique, Eric Dardel, 1952). Basically, he (the author) said that the horizon is not the limit of our vision, because normally, when we think about the horizon we imagine a certain line that is the limit of what we see. He’s talking about the landscape and the space that that landscape takes. If the horizon is not the limit, then it must be the space between the limit we cannot see, and our bodies. He calls this the ‘in between’. So, I think that it’s a really interesting idea because he also talked about the concept which he called ‘a base’ which is our body. He said that there is always something happening between your body and the space’ so it’s not just about thinking about the space but the relationship with the body and the space.’

P: I have also noticed that you assigned the theme of roots a significant role in your work. What was your thought process behind that decision?

D: ‘I was already thinking about ‘roots’ because I am a person that used to travel quite a lot. I have never been in one place for more than two years or so. I have been changing houses so I was always wondering what it feels like to have those ‘roots’. Later on, I started thinking more about ‘roots’. Not just as a beginning for a person but more as an end to a person. It was more related to my personal experiences. There were a few strange experiences that I had that made me think about my death. They were all very dark experiences that got me thinking that ‘roots’ also means being in the ground. I started to think about how I could put all these things together and how I could relate the concept of ‘roots’ to death but also relate to the beginning.’

P: Can you advise the people that are in search of their own ‘roots’?

D: ‘I don’t know. When I came here, I thought by myself that I might be able to talk to a lot of people and ask them ‘what they feel attached to’. Trying to find some answers and responses and maybe being able to hear more answers and ideas would help me come up with my own. I don’t know. Maybe I could ask you? What do you feel like you’re attached to?’

P: I never felt attached to places. I think it’s more about people in my case. I’m very close with my family and my friend circle is quite small so I think I’m attached to people around me but to nature as well. I spend a lot of time in nature, I am interested in flowers, I spend time with animals whenever it is possible, so I guess that is what defines me the most.

Foto door Stijn Terpstra

Photo by Paula Rafalowska

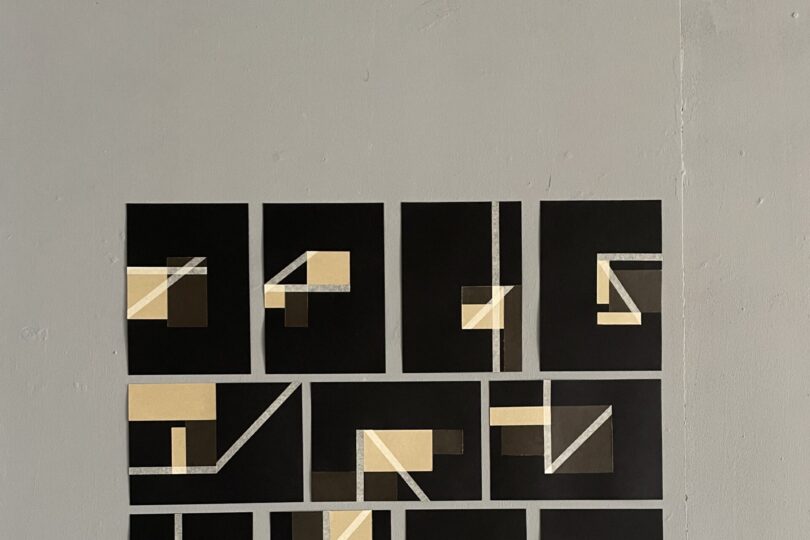

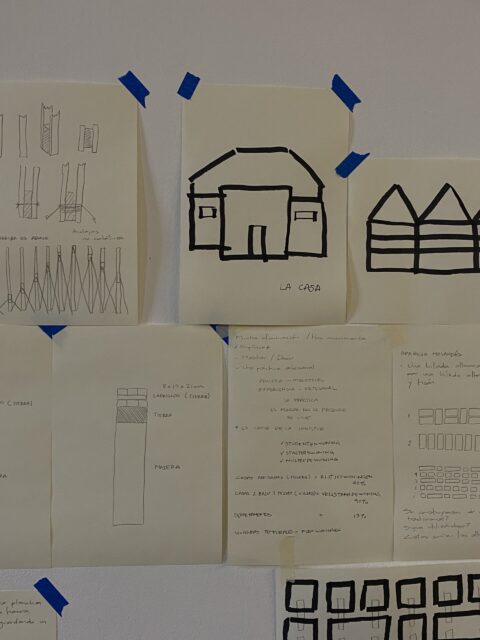

Ventura’s space in StadsGalerij in Breda is a raw space where the contemplation of the landscape happens. The focus of the artist fixes on the notion between the body and its environment. While he explores the possibilities of the landscape, his own work ‘Horizon’ becomes a performance of its own, constantly being documented and recorded. In the vast space of the gallery, walls are covered in sketches of the city. Sometimes there are drawings of trees, birds or buildings. On other pages, the artist added the ideas for the ‘Horizon’ project and described them in detail in Spanish. Moving clockwise, there is a desk with tools, notebooks and even more sketches. This time, the focus is on the centerpiece of the show: wooden constructions connected to dark red bricks by rough pieces of rope. The theme of bricks constantly makes its appearance in relation to the Dutch environment Ventura encountered while staying in Breda.

P: Now that you are so close to ending your project in Breda, has the concept of ‘being in motion’ changed its meaning to you? Is it any different from what you thought before the beginning of the collaboration with Witte Rook?

D: ‘Actually, it has changed a little, because like I said a lot of things have happened to me before. I lived through a very dark scenario for a long time so before I came here, I felt like my life had changed for good. For instance, I will be moving in with my girlfriend when I go back to Mexico. I am used to the idea of changing homes, changing places in life. I don’t know if this will be my place. I’m not sure if I’m going to root in that new place. Coming to Breda is also a change in my life because it allowed me to be able to work. I’m still thinking about being ‘in motion’. It is a very specific and very important component of my work. Not just because of me but because of the nature of my work. Like I said, I can say that I am a sculptor. Lately, I have been thinking that I’m also a performer as well. Most of my installations are very ephemeral so it all happens in space but also in time. This is also related to the concept of ‘inhabit’ that I have been working with. My current work specifically, it’s going to last just for a while and then it’s going to disappear. I think movement and change are related.’

P: In relation to that, I read in your essay on Witte Rook’s website, that you mentioned how your work helps you ‘define your place in the world’. Do you feel like you found any clarity about said ‘place in the world’ after almost finishing this project? In which direction did your contemplation of that concept go?

D: ‘I don’t know if I found a place. I don’t think so but I would say that I found a moment in a place.’

P: Could you walk me through your creative process? How do your ideas turn into reality?

D: ‘I would say that I’m a curious person and that I am always trying to look and to see and to watch my surroundings and what is happening around me. I pay attention to how it is all related to the ideas that I work with. Especially now, with my interest in architecture. I am interested in what you said before about the precise measurements that I need to put certain pieces together in order to create a structure. So I am really interested in how it all works. What it takes to make something. To build something. And also I like to build things with my own hands. I think that especially with this mindset, I am just trying to figure out how to put different parts together in order to get a structure. I don’t know if I answered your question.’

P: Were there any difficulties connected to your creative process? Anything related to the space, materials, people you worked with, etc.?

D: ‘Really just the (Dutch) language. It sounds very strange to me so I think it’s just that.’

P: Have you discovered anything new in relation to your art or self-development that moved your project towards a new direction?

D: ‘Maybe no. Not yet. Because I am a slow person. I need time to digest what is happening around me. To get to know what it is about, that is gonna happen later. For instance, I have just begun working with rope, right before I came here. It is a new material in my project that I wanted to explore more. Before coming to Breda I was working a lot with bricks. I found them to be very interesting. I have worked with bricks before but maybe I could work with bricks again. Just thinking of the experience I had here, maybe I could explore later all that I have learnt while being here.’

P: Did you encounter any major differences while working in the Netherlands in comparison to your work in Mexico, and what were they?

D: ‘Well, besides having a really nice space to make my work in I also got to have the time to myself, without any worries. There’s a lot of differences between Breda and Mexico City but I would say that between The Netherlands and Mexico there are actually some similarities. Have you been to Mexico before?’

P: No, I never had a chance to go there.

D: ‘Well. For instance, the commuting situation. I have stayed in Tilburg for some time. I have been told that it could be an inconvenience, sleeping in Tilburg and working in Breda. I found out that it is only 15 minutes by train and to be honest that is really nothing for me. In Mexico we are used to traveling long distances, at least one hour, for work purposes or to do anything else in fact. So to me those 15 minutes are nothing compared to how much I had to travel for in Mexico. Of course, I found it very interesting that Breda is called a city? And so is Tilburg and many other places. But for me it is more like a village or the countryside because it’s all surrounded by greenery, the trees and nature. You are next to a building and a few meters away you can find horses and farms and chickens and so on. It’s all surrounded by farms and big pieces of land so to me it’s not exactly an urban environment. And yet it is a city. That is the difference that I found.’

Photo by Paula Rafalowska

Photo by Paula Rafalowska

P: Is there anything you are currently missing about Mexico?

D: ‘The food and the weather.’

P: Ahh, that’s understandable. My next question is if you could pinpoint the most memorable experience that you’ve had in Breda so far, what would it be? Did it have any impact on your current project?

D: ‘What really impressed me here was the nature. How the people in The Netherlands have arranged the land. I have been reading a lot of material on how the Dutch have connected the land with the water and what developments they came up with to make their lives more harmonious with the land around them. I read that at least 50% of the land is used for agriculture in The Netherlands. I was very impressed by that in comparison to Mexico. We also have a big agricultural industry in Mexico but for two countries that are based on the same industry there are so many differences. When I asked you if you have been to Mexico before, it was because the difference is very big. Mexico is known for being an industrial, but poor country. Once, when I was on my way to Tilburg, I heard a man on the train say that people living in Breda are arrogant. I don’t know if people here are actually arrogant but what I could see is that for me Breda is a very wealthy city. And I think that in general, The Netherlands is a wealthy country. So in comparison with Mexico that is a huge difference and that really impressed me in a good way and in a bad way as well.’

P: For bad?

D: ‘Yeah, because we don’t really see what we have. We always want more. It is not something happening just in Breda. It is more about the circumstances of being wealthy. For instance, do you really need 2 electric cars? Or maybe even 3, or something like that. Again, this is not an issue just related to Breda. I’m sure there are also electric cars in Mexico but I have never seen as many of them as I have seen here.’

P: What are your plans for the future? In which direction would you like to go with your art? Are there any concepts or mediums that you would like to explore deeper?

D: ‘I was thinking of doing another Master’s degree. But this time in Architecture. I studied visual art, but since my art process is connected to making structures, I was thinking that it would be a good idea to have a proper education. Or maybe not even a proper education but just know the basics of architecture and have good, strong skills in making structures. Maybe learn Maths or something like that because I don’t know much about it either. I don’t want to be an architect but I do want to make strong structures because ‘Horizon’ is a long-term project and what I picture in my mind for the future are some bigger outdoors pieces. Maybe large-scale and I have to be sure that they are secure with all my new knowledge. And maybe also I have been interested in something called ‘perma cultura’ ‘biostructure’ which is related to the use of natural and recycled materials and how it all is related to the land. Everything comes from the Earth. I want to be more responsible and more careful with the land.’

Paula Rafalowska, Breda, March 2024